Moustroll

Good movie but grossly overrated

ThedevilChoose

When a movie has you begging for it to end not even half way through it's pure crap. We've all seen this movie and this characters millions of times, nothing new in it. Don't waste your time.

Mandeep Tyson

The acting in this movie is really good.

Juana

what a terribly boring film. I'm sorry but this is absolutely not deserving of best picture and will be forgotten quickly. Entertaining and engaging cinema? No. Nothing performances with flat faces and mistaking silence for subtlety.

Yashua Kimbrough (jimniexperience)

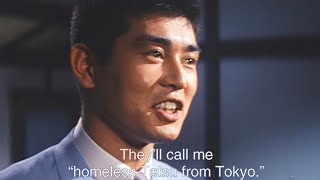

The cinematography that inspired Quentin Tarantino , Johnnie To , and Takeshi Kitano ... Violent, cool, jazzy, colorful, gangster, clubs, shootouts, guns with codes ..Tetsu lives a charmed life by the side of his boss Mr. Kurata. But when his boss disbands the group rival Otsuka wants to take over . When Tetsu declines his offer to join his gang Otsuka sets out a personal path to destroy Tetsu and Kurata. He takes the mortgage of Kurata building by force. When people start dying and gangs begin forming alliances, Tetsu decides to get out of dodge and become a drifter .Otsuka , obsessed with Tetsu's demise, sends Viper (equally obsessed with Tetsu) to take him out. Along Tetsu's journey he participates in a shootout in the snowy mountains, befriends a drifter from Otsuka gang Shooting Star, and gets into a bar fight in South Japan.Otsuka strongarms Kurata into rubbing out Tetsu. Tetsu gets word his boss betrayed him and sets off back to Toyko. He returns to find Otsuka in his club beating his girl, his former boss by his side. Thee final shootout ensues

Polaris_DiB

A crime boss and one of his men decide to go straight. In gangster-movie land, of course, their decision is met with conflict as another, rival gang is basically hellbent in messing up everyone's Christmas by bringing the boss's main man, Tetsu, back into the world of violence he's trying to escape. Of course, Tetsu isn't very much of a pushover--in two ways, being that he's both stuck to his decision and also capable of wiping out entire roomfulls of baddies with grace and acumen and a small gun that only fires ten meters.Suzuki's Tokyo Drifter is called a "free-jazz gangster film", and that fits the description to a tee. It starts out mostly like a French gangster film, with airs of Melville, then slowly escalates into comedy, violence, and more and more mod set pieces, showing influences throughout cinematic history. It wouldn't even really be fair to say it has any one theme or direction, so it also could fit the improvisation view of jazz.There are some really stunning moments, most of them involving the set-pieces. Suzuki seems to delight in art decor and mod style. He loves bright, striking colors, and his camera work is at times quite flamboyant (the half-gelled lenses during those scenes in the snow come to mind). If anything, this movie is like candy--delicious to the eyes, but would probably have been sickening if there had been too much of it. However, in good sleazy movie form, Suzuki keeps the length to just under an hour and a half, providing respites throughout in some surprisingly tender scenes.--PolarisDiB

Graham Greene

Much of Tokyo Drifter (1966) requires a certain sense of cultural background and historical context in order to be better appreciated; otherwise, it most probably seems vapid, dated and entirely incoherent. You have to appreciate the fact that for the first part of his career, director Seijun Suzuki was a contract player for Nikkatsu Pictures, and largely obligated contractually to take any project offered to him, regardless of plot, concept or theme. He was also working under fairly strict conditions in order to produce the biggest financial turnover, whilst simultaneously striving to give his films a certain sense of character or individuality to make them stand out against the other, identikit youth films being produced by Nikkatsu at that particular time. By the mid-1960's he'd already begun to push his films further into more personal, idiosyncratic directions; experimenting with colour on Youth of the Beast (1963) and composition in The Story of a Prostitute (1965), as well as experimenting with more theatrical uses of lighting and location design on the classic Gate of Flesh (1964).Most of these stylistic flourishes came from his interest in Kabuki theatre, with Suzuki transposing the artificial, ornate and entirely abstract world of those productions to the gritty and violent streets of his low-budget B-pictures. It is important to keep in mind also that these films were incredibly cheap to make and certainly not considered to be "prestige pictures". Think of the hundreds of other films being released by the same company at the same time and ask yourself why these films aren't getting the same kind of posthumous attention in the west. The real reason is the context. Suzuki transcended the limitations of what was required of his work; instilling it with a personal style and a larger than life sense of exuberance that resonates with anyone who can truly appreciate the magic and power of cinema. This is apparent right from the start of Tokyo Drifter, as a black and white sequence of betrayal sets up the mood of gritty violence, punctuated by stark abstraction. The scene is vague and enigmatic; choreographed in such a way as to suggest pastiche, but still managing to remain fairly brutal. Suzuki also wastes no time throwing us into this overly complicated narrative, in which the turf war between two rival Yakuza fractions spirals out of control and causes grief for a loyal young thug trying to do the right thing, whilst still attempting to remain faithful to his boss.However, what is most remarkable about this scene, and about the film in general, is Suzuki's anarchic and unconventional approach to location and production design, as well as his fragmented bursts of editing and his masterful use of cinematography. The opening scene fools us into thinking that this will be another run of the mill, low-budget gang-thriller in gritty black and white. However, as the central character drops down on one knee to fire a succession of shots past the camera at an off-screen foe, we cut briefly to a shot of bold, dizzying colour. After the opening scene has played out, the film cuts to that catchy title song and the film switches to colour full time. This juxtaposition is a jarring one, and establishes the mood and tone that Suzuki had in mind for us, as the rest of the film continues these ideas of abstraction, exuberance and the utterly unconventional. The cinematography, design, editing and costumes are fantastic throughout, with Suzuki and his team using bold, primary colours that create an almost comic-strip like quality, whilst the use of theatrical lighting, camera movement and those epic, cinemascope compositions turn a backstreet battle for power into an epic parable of almost Shakespearian proportions.If you're already familiar with Japanese Yakuza cinema, from the grittier, more hard-hitting films of Kinji Fukasaku, to the restless experimentations of Takashi Miike, or indeed, the unconventional gang cinema of Takeshi Kitano, then you'll already know what to expect from the presentation of character and theme established by Suzuki herein. So, we have loyalty, betrayal, power, corruption, brotherhood and retribution alongside the central notion of a once-violent character attempting to remove himself from a world that he can no longer understand. Obviously, given the conventions of the genre, he can never quite escape this world, and indeed, it is here where the conflict of the film will arise. However, such notions of story and character are sure to come secondary to the overwhelming power of Suzuki's images; which suggest, as one reviewer put it, "the spirit of a youthful Jean Luc Godard directing Point Blank (1967) from a script by Stan Lee".Criticisms that Suzuki can't tell a coherent story are puerile and go against every notion of what cinema is and what cinema should attain to. You simply cannot judge a filmmaker off the strengths and weaknesses of a single film, especially one that already has a reputation as being one of his most radical and slyly anarchic. It's like dismissing the work of Takashi Miike after only having seen Fudoh: A New Generation (1996) or Dead or Alive (1999), or even dismissing Tarantino off the back of Death Proof (2007) or Kill Bill (2003). There are plenty of films from Suzuki in which the story is a primary concern; however, with Tokyo Drifter he was attempting something different, something more revolutionary. A pure slice of psychedelic 60's chic in the pop art tradition, with shoot-outs, fist fights, fragmented editing and some truly intoxicating colours.

BJJManchester

A basically routine Japanese gangster melodrama,TOKYO DRIFTER has been recognised as a classic example of 'B' picture film-making by dedicated film scholars and cultists in the West,along with Seijun Suzuki's other Yakuza masterpiece,BRANDED TO KILL.It has a confusing,if deliberately ambiguous narrative which takes considerable following,which is the film's only major Achilles heel.Where TOKYO DRIFTER succeeds is in it's clever production design,lighting,stylised action,superb photography and imagery.Suzuki has ensured that,if we the audience are hopelessly led astray with the murky goings on with the plot,we can still admire it's dazzling style and colour,plus some other quirky touches,such as gags about hairdryers,a John Wayne-like Western barroom brawl,and an oddly memorable theme song.This is insistently played throughout the film,but still pleasantly haunts the mind despite it's repetition.After BRANDED TO KILL,Suzuki fell foul of his bosses and was sacked for making such unusual,auteur-style Yakuza melodramas.This is a great shame as he did not direct another film for some years afterwards,depriving us all of his uniquely styled gems,possibly when he was creatively at his most fertile.It is all the more encouraging,that,in his 80's,there are still new admirers and retrospectives of his work(there was one quite recently in London,with Suzuki making a welcome personal appearance despite failing health),and his most up to date work,PRINCESS RACCOON,was generally given considerable praise.Let's hope that this previously neglected master stylist of Japanese,if not World,cinema,will finally be given his dues.RATING:7 and a Half out of 10.