Jeanskynebu

the audience applauded

FuzzyTagz

If the ambition is to provide two hours of instantly forgettable, popcorn-munching escapism, it succeeds.

Brenda

The plot isn't so bad, but the pace of storytelling is too slow which makes people bored. Certain moments are so obvious and unnecessary for the main plot. I would've fast-forwarded those moments if it was an online streaming. The ending looks like implying a sequel, not sure if this movie will get one

Billy Ollie

Through painfully honest and emotional moments, the movie becomes irresistibly relatable

spguest

Just watched this movie for the third or fourth time and can't understand it's relatively low rating. The acting, the direction, just the sheer scale of the adaptation is simply stunning.

SnoopyStyle

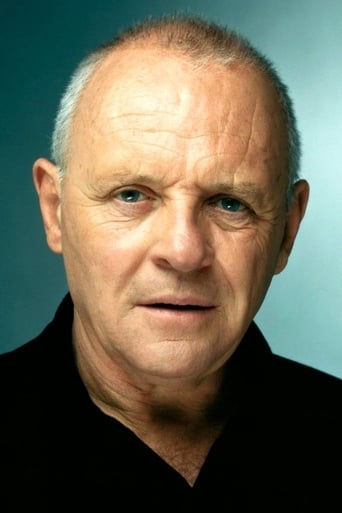

It's a mix of Ancient Rome and modern fascist Italy. General Titus Andronicus (Anthony Hopkins) returns from his campaign with hostages, Queen of the Goths Tamora (Jessica Lange) and her sons. Titus sacrifices her oldest son. Saturninus (Alan Cumming) and Bassianus (James Frain) compete over the empty throne. Senator Marcus Andronicus (Colm Feore) nominates his brother Titus for the crown. Prideful Saturninus is angered and Bassianus is supportive. Titus relinquishes the honor to Saturninus who claims Titus' daughter Lavinia (Laura Fraser) despite the fact that she's already betrothed to Bassianus. To everyone's shock, Saturninus frees Tamora and her sons. Bassianus flees with Lavinia with the help of Titus' sons. Duty bound Titus even kills one of his own sons to try to stop them. Saturninus takes Tamora as his replacement bride as she plots her revenge on Titus.Director Julie Taymor has put as much costumes, great actors, dressed up sets as she can but it's still very stagey. It can't escape from being a play. It's interesting for a little while but it wears thin. There are not enough people and not enough grandeur. The dialog is still Shakespearian. It is a brutal violent play. The actors do a great job but this is a play, not a movie.

chaos-rampant

This is a handsome, sorrowful, flourishing, heavyhanded retelling of Shakespeare. I went for a walk afterwards and it felt cleansing to breathe in the cool night air after all the despair and hate of this. Much of it comes down to the play itself. It is bloody and mad, heavyhanded itself. A gloried general who puts Rome above his sons. A vengeful mother and queen who will not return pity when she was given scorn. A pathetic king, a monstrous moor, and various sons and daughters as playthings for the mad.It is clumsy in spots. The whole ruse in the forest with slain Bassianus must have felt far fetched to even Shakespeare. And a Roman general who slips out and returns against Rome with an army of the Goths he helped vanquish a few months ago? But overall it is powerful, gripping stuff because it's in the right hands here.The question how to visualize Shakespeare must be as old as the medium. The filmmaker here made a simple concession. Keep the original language. This means she can't film the metaphor, which would make a superb film of itself. Her brilliant choice was to create a modern stage for it. A Roman orgy plays out like a party from the roaring 20s. Cars and cigarettes coexist with tunics and armor. But the main thrust is still cthonic and medean.We don't have a calligraphic weave where character urges appear as encounter. But she has managed to address another, equally difficult problem of cinematic narrative. So many films are a passive exchange. What she has done in this odd way is carve a vital space for the story that avoids the pitfalls of both the usual period piece and on the opposite end the arbitrary imagination of something like the Cremaster films.It jars for a while but settles as a coherent world that is different enough to demand attention to it. It feels alive, freed from a historic stage, neither realistic nor without reality, puzzling the logical thought (why cars?) yet remaining implicitly recognizable for the eye.And yet it's all that rich, image-based language of the original that I find myself drawn to.In Shakespeare's time, plays were apparently performed with only bare essentials of stage craft. I know very little about him and the time, but this film surprised me enough to want to change that. Anyway, the word carried the cinematic stitch, the visual horizons. Here we have both word and stream of images, which may dampen the impact of the first. Yet I urge you to really pay attention to the word here, always in conjunction with the story. On the top dramatic layer we have sin and madness. Deep down, though, it is all about realizing what is truly vital and matters in life: intuition, not structure. It is not the loss of queendom for her, nor for Titus the loss of prestige that truly hurt. What Titus deprives of the Goth queen and is turn torn from him tenfold is this human background of connection to loved ones that we often take for granted as we plot careers, this being love. Not the same as passion, it is exactly the sense I have when I feel happy, the spontaneous assurance provided by things, the deep anchorage in the world that can only come from caring about things other than myself.This is not poetry, but mechanics of awareness. Being happy and whole entails a sense of rootedness in the world around me.The play is stitched throughout with metaphors about exactly this: the earth accepting rain, trees blowing in the wind, gnats flying in front of the sun, rivers overflowing their banks, branches, deer, earth, rain. Wonderful, wonderful cinematic flows in words. It is not the word itself that appeals, the literary quality. The word carries the insight, capacity for horizon. All cull from nature the same observation, the same motif. Transient, violent motion yet always anchored in the world with capacity to bear it.My world is Taoist, out of personal choice, worlds apart from Shakespeare. I am always riveted by his work but need that cleansing walk afterwards that restores things. And yet here I find him drawn to the same realization as the Chinese masters in their meditation, that of a (perceptive) field beyond suffering and nonsuffering where things hold each other in place by virtue of being what they are.Shakespeare's Tao.

ritachouchou

the modern version of TA simplifies the story from the declining of an absurd world to the downfall of a Roman general, hence fundamentally subverting the tragic significance. The transformation lies in the introduction of a modern perspective. Titus begins with a boy wearing a paper veil resembling the Klan, eating at a table, while playing a collection of toy soldiers including both Roman warriors and modern troops. He is frightened by a bomb blast, rescued, and whisked away to Ancient Rome. With the boy assuming the character of young Lucius, the film is constantly directed through his angle, from his first surprise at the Terracotta Army, his excitement in welcoming the election, to his witty response after killing the fly (originally done by Marcus). Furthermore, the film ends with him carrying Aaron's child, leaving the coliseum, and walking toward sunrise. Here the film inserts a comparison between the tragic massacre in Titus and the boy's slaughter of toys with milk, cake, and tomato sauce at the very beginning. His final left echoes his sudden arrival, closes the Pandora Box of this anachronistic structure, and actually pushes the timeless violence away into a finished fantasy. Once again, the director voices over Shakespeare by symbolizing the modern boy as "a tentative hope for the future." Inevitably, it defuses brutal violence and beastly humanity that are so intensified in the play. However, one should notice Lucius' succeeding and restoring order are as temporary as Lavinia's writing in the sad. Shakespeare left Aaron with no repenting "I am no baby… Ten thousand worse than ever et I did / Would I perform if I might have my will" (V.iii.184-87) and he casted way Tamora's corpse with "No funeral rite, nor man in mourning weed, / No mournful bell shall ring her burial." (V.iii.194-96) Rome is in deadly silence. Salvation comes where. The text embodies a more profound understanding of the historical setting behind TA tragedy, where the civilized Rome is under the irresistible process of declining, and eventually overrun by the barbarian northerners, the Germanic. Hence, the modern concern upon love and peace within the twentieth century re-evaluation context fundamentally lessens the ultimate desperation and disorder presented by this specific ancient moment, and is likely to be both extravagant and ironic.