Katrina Fleming

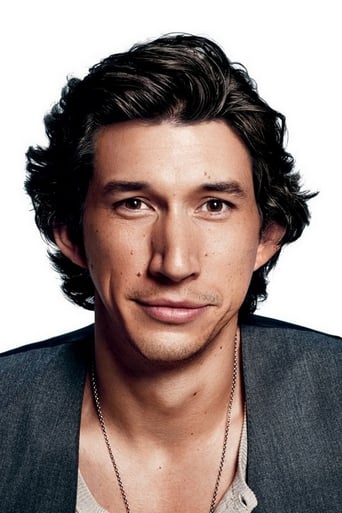

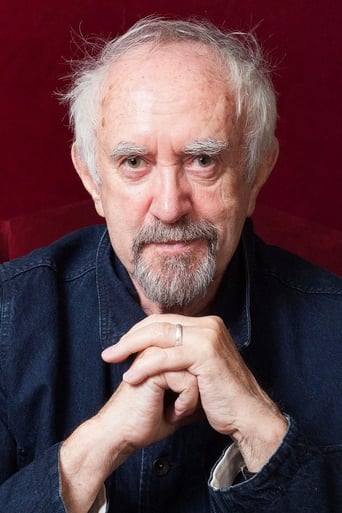

If you know the story of Don Quixote, the Man from LaMancha you will find this film to be very clever in its layering of the original tale intertwined with a new tale that is infused about a narcissistic director (Adam Driver) who has lost his creative mojo whilst filming a feature film about Don Quixote in Spain. True to its original intent, it is a hybrid of reality and fantasy with the cruelties of the world as a backdrop to what could be with a touch of madness. It has much to say about youthful and brave creativity, and the artistic freedom that comes from true independence and the necessity of reframing your reality to match your circumstance. Love, passion, friendship, empathy, and generosity of spirit are explored in a modern version of the Spanish Inquisition. The jailhouse sequences are sublime in their mash up of real and unreal. It is a clever, witty and multilayered script with much for the literate fan to digest and plenty for newcomers to the tale to learn. Jonathan Price is perfect as Don Quixote and Adam Driver manages to deliver skepticism, narcissism and empathy along an increasingly complex tightrope with ease. The script is a marvel and the directing and edit are to be applauded. I don't know what the film offers people unfamiliar with the original story- but as I've been waiting for many years to see this film I can say it does not disappoint, I'll be thinking about it for a long, long time. Well done Terry Gillem

RResende

As humans, we create stories to represent ourselves, and to grasp the world that we don't understand. Arguably everything that we call art is in the end some sort of narrative, some system created to explain aspects that we didn't understand. Those stories are abstractions, a simplification that we use to reach deeper, to make order out of the apparent chaos.

At the end of the 16th century, a growing number of european unrelated artists were working on novel revolutionary ways to represent ourselves, changing how we explain who we are and actually changing thus "who" we are. Cervantes, Shakespeare, Velázquez, and others, were giving us new modes of abstraction, new modes of (self) presentation. Mirrors.

Quixote is all about that. A story about someone who creates himself based on other stories. A character who wipes the definition of reality by merging it with his own reality, co created by him and all the other storytellers who created the stories that drove him to his paralell reality. Then, the confrontation of his invented world with the reality of the world that surrounds me - the common depiction of this is having the "real" world take Quixote as "crazy". That's an extra simplification, an extra abstraction. Irony.

Cinema could be in theory a fine medium to translate Quixote into, and that has been tried a lot of times. Now we have this Gilliam attempt, and the layers of this project, its own story, add a bit more to the excitment of Cervantes. Some information is required:

Gilliam had tried to do this project before. It failed for a number of pedestrian reasons. That failed project has a story of its own, and generated a film about its (attempted) making. Now he completes it, and the synopsis could go like this:

A filmmaker (Gilliam) is making a film, based on Quixote, after having failed to do it 16 years ago (we are one layer deep from reality). This new film is about a filmmaker (Toby) who is doing a commercial film of Quixote in Spain (film within a film, 2 layers deep). We learn that the first images we see are actually part of a film within by a breaking of the 4th wall Truffaut style. Toby had done a student version of Quixote 10 years before, and that film sort of magically pops back in his life. He watches this other Quixote versions, we get glimpses of it (another film within the film, still 2 layers deep but paralell to the other film). As Toby visits the village where he had made that student film, he finds out that film affected the reality of all the people involved in it: the actor from Quixote believes himself to BE Quixote, Toby's girl/lover had her life pretty much destroyed by having done the film, and so on. This new discovered reality, provoked by Toby's student film, invades the reality of Toby's life, and he is literally taken into the old film (he rediscovers the old actor/Quixote watching his film) and mistaken by Sancho. After this we see the unfolding of superficially Fellini inspired episodes, of reality blurred layers, plays on "what's real", and a Wellesian party on a remarkable building, near the end (more on that soon). In doing that, Gilliam uses a bunch of tricks, some well used, some not so. None of them is completely novel, i think. So we have bits of self-reference, such as when Toby literally removes english language subtitles from the screen. In one scene he claims to have written the lines that Quixote is telling him (that one is masterful as dialogue serving the concept).The gypsy who give Toby the dvd and keeps coming up is a fundamental character. A wizard of sorts, i believe a kind of surrogate to Cervantes on screen, a master puppeteer who manipulates and drives the narrative, all the way to the end. That's a genius character.I appreciate that Gilliam is a risk taker. This is a crazy imperfect film, which has some beautiful images. What I think Gilliam did well was to place the reluctant Sancho/Toby as a film director, and apparently the one through whose eyes we watch the story. That is self-referential in the way Cervantes conceived it, i think. So many people have misunderstood Sancho as some sort of "comic sidekick", the validation of Quixote's madness, and so on. But he is in fact the holder of the keys of paradise, the man who chooses to go mad, the character who sees both realities, and chooses to be in both almost always at the same time. He is one of the most powerful fiction characters ever, he is all of us at some moment of our lives, and he truly is the best character of Cervantes, and i believe the one where Cervantes projected his own self more clearly. In the original Gilliam project, Depp was going to play the part. Oh I wish he had... That's my personal film. Watching this new version i was simply imagining how Depp would handle the shifting between realities, between layers of fantasy. Driver is not quite up to the part. Pitty...I also don't understand why he had to channel the representation of Spain as a "Carmenesque" world. Carmen is after all a collection of spanish (mostly andalusian) clichés filtered through the eyes of a frenchman. They became popular in Europe inthe 19th century and still represent the images that most people associate with the meaningless concept of "spain" (bullfight, hot tempered love, sun, harshness and a certain concept of tragic fate). It is sadly ironic that Gilliam, who has some nice visual intuitions, and solid storytelling complex concepts fell into this so easily avoidable trap. I suppose this won't be such a problem for someone who doesn't now Spain, or watched it only through a touristic gaze (which is shamelessly sponsored by the very spanish government in their promotion of the country).Visually, he mixes his own well established style, the odd wide angles (often wellesian) with the by now required standard Quixote scenery... that thing about a guy in a horse and another in a mule riding the desert against sun light. But than he brings for his delirious climax his architectural eye, and that's what grabbed me more:Our characters are taken to an obnoxious russian millionaire's palace. The event is a masquerade ball (Arkadin style), where pretending to be Quixote won't apparently seem so crazy. That palace is a remarkable building. It's a convent and church, in Portugal, built across several centuries, with many of our best architects from each time participating in it. It is a collage of styles, each one integrating in the whole while retaining its own character. He films mostly the central church, a Templary octogonal church, a mystical powerful space, dynamic in that it invites moving around it; and 2 of the four big cloisters. The whole place has always been the center of strong spiritual representations that predate Christianity in Portugal, and it still retains its power. I'm thankful that one of the great film architects that we have got to film it. This is probably the second best use of portuguese architecture in cinema, after Welles filmed his Othello's "sauna scene" in a magical light portuguese cistern in Morocco.Anyway Gilliam opposes openness (desert, big landscapes, etc.) to the tragedy of the architectural space, where the most intense plot points happen. First the humilliation and breaking of Quixote's fantasy (check how that is ostensibly show as a film set, with visible lights, artificial props, SD indications, etc.). And than, the inevitable death of Quixote. We close our final (circular) narrative layer here: the shattered Toby, who killed Quixote, assumes his invented reality, and becomes Quixote himself, with his lover as Sancho. They ride with the former Quixote's body to bury him, and the meet the giants that Gilliam had shot for his first failed attempt. We actually see the test footage he had made. We are left there, with our Toby turned Sancho turned Quixote literally entering the film that Gilliam never made. That was masterful.I will choose Welles and Fellini over Gilliam. This is a flawed uncontrolled film. But Gilliam is all about that: letting his intuition (mostly visual) contaminate all the rest. I respect him. Watch this, but consider all the layers. It will make it richer, i think.