James Hitchcock

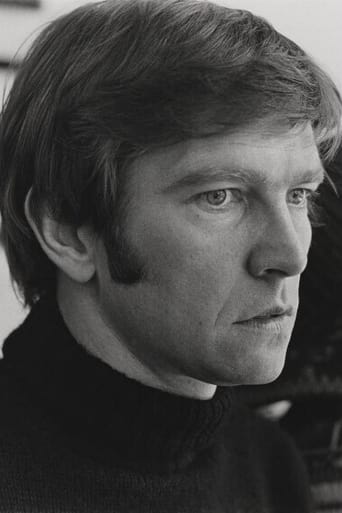

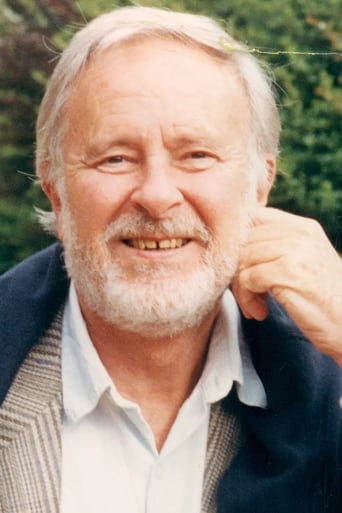

Alan Sillitoe seems to have gone down in literary history as a two-hit wonder, the two hits being his first two works, the novel "Saturday Night and Sunday Morning" and the short-story collection, "The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner". Few, if any, of his later works achieved the same success. In the late fifties and early sixties, however, he was a leading light in what became known as the "kitchen sink" social-realist movement in English literature, and both books became key texts of that movement. The British cinema was going through a similar social-realist phase at around the same time, so (like several other key kitchen-sink texts, such as Shelagh Delaney's "A Taste of Honey" and Stan Barstow's "A Kind of Loving") both "Saturday Night..." and "The Loneliness..." were inevitably adapted for the screen. "The Loneliness..." tells the story of Colin Smith, a youth from a working-class Nottingham family, who is sentenced to a term in borstal for burgling a bakery. (A "borstal" at this period was a special prison for young offenders). In the original short story he was simply called "Smith", but Sillitoe, who also wrote the screenplay, evidently felt that he needed a Christian name for the screen. The film is essentially a study of class conflicts in the Britain of the late 1950s and early 1960s. The two main characters are Colin and the Governor of the borstal. The Governor is, on the surface at least, a humane and decent man. He claims that his job is to reform and rehabilitate the young men in his charge rather than to punish them. The Governor's ambition is to run his borstal along the lines of a public school. (His accent suggests that he is probably a public schoolboy himself). He is keen to encourage his boys to take up sport as part of his rehabilitation programme, and Colin becomes a protégé of his when he discovers that the young man is a talented athlete. Colin is entered into a cross-country race in an athletics meeting against the boys of a nearby public school. The account of Colin's time in the borstal is intercut with a series of flashbacks showing his previous life in Nottingham. An event which had a great effect on him was the death of his father, not because he had any great affection for the old man but because he saw him as a symbol of the downtrodden, put-upon working-class little man. From what we learn, Smith senior appears to have worked all his life in a badly-paid dead-end factory job, with little to show for his hard work. He was badly treated by his bosses and cuckolded by his sluttish, sharp-tongued wife who moved one of her lovers into the family home almost as soon as he was dead. (Colin may have had no great affection for his father, but he positively detests his mother). Colin's resentment of "the System" may derive from a determination not to allow himself to be trapped in the same way as his father was. I have always been in two minds about Colin's famous final act of rebellion, but then I think that Sillitoe deliberately intended it to be ambiguous. On the one hand, some have seen it as a magnificent revolt against the System and against the Governor and his old-school-tie Establishment values. Others, however, have seen it as a pointless gesture by a young man who actively wants to be a loser because he is too cowardly, or too apathetic, to be anything else. I think that Sillitoe also wanted us to be in two minds about Colin himself. For all his talk of working-class solidarity, he is actually very self-centred. He can talk the language of "them and us" when what he really means is "them and me". When he robs the bakery he gives no thought to the workers whose wages he is stealing; his only thought is to spend the proceeds on a trip to Skegness with his partner-in-crime and their girlfriends. The alacrity with which the police make him their Number One suspect, even when they have no hard evidence against him, suggests that this is far from being his first brush with the law. Sillitoe himself had left-wing sympathies, as did the director Tony Richardson, but he may have intended Colin as a portrayal of the "phoney radical" who uses the language of political protest in order to justify his own selfishness and criminality. I think that we are also supposed to see the Governor as an ambiguous figure. On the surface he may seem decent, but it is implied that beneath this surface veneer he is less humane than he seems and that he turns a blind eye to brutality carried out by his officers against the inmates. He talks about his concern for his charges, but we suspect that he may only care about a favoured few, especially those who share his interest in sport. If Colin is a phoney radical, the Governor is a phoney liberal. There are two fine performances, one from that pillar of the British theatrical Establishment Sir Michael Redgrave as the Governor, a pillar of the British penal Establishment, and the other from Tom Courtenay, one of the emerging Angry Young Actors of the early sixties, as the angry young Colin. The contrast between their two very different styles of acting- Redgrave superficially gentlemanly and urbane, Courtenay feral and aggressive- symbolises the clash of social classes and of values which lies at the heart of this fine film. 8/10

avik-basu1889

A poignant exploration of the British class structure in the 60s as well as a study of the disillusionment of the 'angry young man' of the working class. The story is interesting, but the direction as well as the musical choices at times is a bit weak. Nevertheless it's still worth recommending.

John Henrici

This has always been one of my favorite films. I saw it as a kid on Million Dollar Movie from New York. they would.show.the same film every night for a week. I don't know how many times I saw it but I was mesmerized by the bleak b/w landscape that reminded me so much of my hometown in Edison, NJ. It was the first time I'd ever been shown that bleakness could be beautiful. it was also astonishing to see the interiors of Col's house. It made me feel like a millionaire. And, as someone else said, the scene of Col burning the money was stunning to me, night after night.and then I never saw the film again for 20 years. I saw it in the TV listings and I was afraid to watch it. I'd built it up so big in my mind that I was afraid it'd be a letdown. when I saw it again I was shocked at how good it still was. when I was a kid I saw Col's actions at the end as a grand gesture to authority. Lately I see him as someone who is just stuck. He can't decide. Yeah, I know he smirks at the headmaster in the scene, but I think it's bravado. with all those voices in his head it's as much can't as won't consummate the act. Whatever, a killer movie for all time.

Klaus Ming

UK 104m, B&W Director: Tony Richardson; Cast: Tom Courtenay, Michael Redgrave, James Bolam, Ray Austin, John Thaw, Alec McCowenThe Loneliness of a Long Distance Runner is a brilliant expose of social class, poverty and youth disillusionment in Britain during the early 1960s. Sentenced to reform school for petty crimes, Colin Smith is a rebellious youth from a poor family who is encouraged by the headmaster to train for an inter-school cross-country championship race. During Colin's many hours of training, we witness in flashback the events which led to his incarceration, and the underlying reasons for his defiance against authority. Taking advantage of special privileges to train, Colin uses the freedom to escape from his grim surroundings. Recognizing that he is being used, he surprises everyone by with a wonderfully unforgettable act of defiance at the finish of the championship race (Klaus Ming September 2013).