Pluskylang

Great Film overall

Gutsycurene

Fanciful, disturbing, and wildly original, it announces the arrival of a fresh, bold voice in American cinema.

Lucia Ayala

It's simply great fun, a winsome film and an occasionally over-the-top luxury fantasy that never flags.

Gary

The movie's not perfect, but it sticks the landing of its message. It was engaging - thrilling at times - and I personally thought it was a great time.

Sergeant_Tibbs

The Earrings of Madame De is probably the most integral classic that I hadn't seen, not necessarily for its importance in cinema history but in its influence with my contemporary favourites. It's clear to see its fingerprints all over the work of Wes Anderson and Paul Thomas Anderson for instance and its technical bravura is the easiest aspect to find immediately enthralling. Letter From An Unknown Woman had hints of Ophuls' style, but Madame De is full throttle with his marvellous controlled hand with its swirling camera-work complimenting the extravagant production and costume design. There's a wonderful romance in how it handles fate and coincidence in its satisfying full-circle structure, but there's a tender bittersweetness in how it shows finding love through another love. The eventual tragedy is counter-balanced by good humour despite the admittedly unlikeable characters. But that just feeds into the superficiality of the film's construction and how it doesn't matter how beautiful something is, as demonstrated by what the earrings mean to Madame De by the end. This is excellent filmmaking and I must watch more Ophuls immediately.9/10

MartinHafer

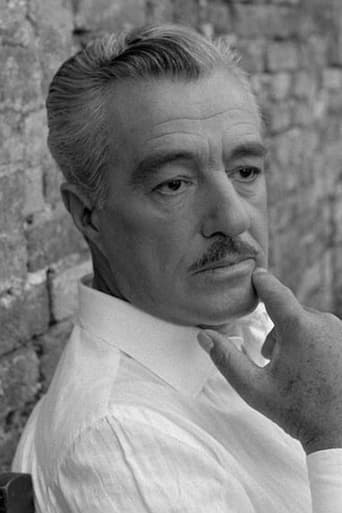

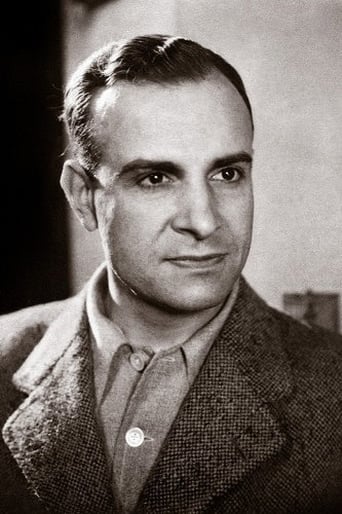

Okay. Time for me to make a bit of a speech. I love French films and have noticed something about Max Ophüls' films (yes, I know he was German but made films in France). Practically all of his famous films have to do with adultery or prostitution. Now I guess I am a pretty old fashioned guy, but I don't enjoy scripts about these topics. So, although I'll admit he was a master storyteller, I just had a hard time getting into the stories or caring about the characters. Who cares about the husband or wife in this film? They both were pretty despicable rich folks who seemed to have nothing to do with their time but gamble, shoot people and flirt with people other than their spouses. What idiots.The film is about a General and his wife the Comptese. They both have every reason to be happy and you think through the first part of the film that they are. But, you do know that the Comptese is unwise--she's run up gambling debts and cannot pay for them without telling her husband. They CAN afford to pay but she doesn't want him to know, so she sells her prize diamond earrings. Then, she claims they were lost. Later, the husband learns that she sold them and buys them back from the man who bought them. Then, he gives them to his mistress. In the meantime, she begins an affair with another man and he is able to buy the earrings and give them to her! There's a bit more to this and there is a sad ending, but I'll let you see this for yourself.I can't fault the film's acting. It stars Danielle Darrieux, Charles Boyer and Vittorio De Sica--all very fine actors. And, as I said above, the film looked lovely--really, really nice. I just didn't care about the characters and so I have a hard time really endorsing the film wholeheartedly. Worth seeing, but not a must-see.

WinterMaiden

There is little of praise I can add to what others have said. I would like to address the comments of those who don't like the film because they find Louise unworthy of their admiration or sympathy. (There are two threads on the board that raise the same objection, and one quotes a review that calls her a "dick.")Do you feel sympathy for Humbert Humbert? Or for Emma Bovary? Or for Anna Karenina? Or for the Vicomte de Valmont? People are certainly free not to like the directing style of Max Ophuls or the performance styles of his actors. But in the negative reactions to this film, and especially to the character of Louise, I detect a strong whiff of anachronistic response, and an inability to see the film in the context of its time and place, not to mention the characters in the context of their society. It also seems to me that many people have a sort of high school notion that you have to find a character admirable in order to feel sorry for her. Or, for that matter, that you have to feel sympathy for a character in order to be moved by her story.The irony of "Madame de. . ." is that it turns out that the character with the deepest and most constant emotions is the General, who has concealed the depth of his feelings for Louise because it is not the fashion to be in love with one's own wife. He follows the rules; he has mistresses; he doesn't mind Louise's lovers too much as long she too follows the rules. He can't handle it when she strays outside the lines, and it is HIS behavior, not hers, that finally ruins them all.The art of "Madame de..." is that the lush setting and sense of a society that lives on ersatz emotion prepares us to be caught up in the ecstasy of Louise's immolation as the emotions become real. That doesn't mean that the Baron is really the Romeo to her Juliet, or that (artistically speaking) he needs to be. In her review of "The Story of Adèle H.," Pauline Kael comments on what a pathetically inadequate object of obsession Lt. Pinson constitutes. Indeed, late in the film, when Adèle passes him on the street, she doesn't even notice him. The Baron is also a rather bland love object, and it is true that we have little sense of how far their affair has progressed, or if he would even want Louise to leave her husband for him. (That is not, after all, how the game is played.) In the Garbo "Camille," Robert Taylor's Armand is utterly unworthy of her, and I've never seen a version of "Anna Karenina" where the Vronsky seemed worth ruining oneself over--or who, for that matter, really seemed to WANT Anna to leave her husband for him.Louise's tragedy is that her understanding of the game, of which she is a typically petty and only somewhat skilled player (she has, after all, already skirted the edge of ruin by falling deeply into debt), does not prepare her for actual love. Once there she tries to behave well, but events spiral out of the control of all the characters once they are outside of the predictable game. We don't even have to see a redemption in the completeness with which she gives herself up to her love, or her making herself ill over it; her behavior is by and large selfish and unconcerned with the feelings of anyone other than herself. If not a redemption she does have a kind of saving grace: she doesn't ask for pity or understanding (although she does ask for forgiveness), and she does achieve a kind of understanding of herself when she admits near the end that she is hopelessly vain. What makes "Madame de. . ." a great film, though, is how we see the General, Louise, and even the bland Baron become human as they step outside the rules of the game, and the way in which the art of Ophuls prepares us for the exaltation of Louise's destruction. You don't have to pity her to be moved by the emotion of it. You may even find a dreadful comedy in it, as one does with Humbert. Humbert knows how unworthy he is as a figure of tragedy; Valmont realizes with a bitter sense of irony that he has destroyed himself with his own clever pettiness. Louise lacks those levels of insight, as well as their degree of villainy, but her lack of credentials to be a great heroine is itself moving. At the end, when she finally destroys herself, it seems to be, at last, in her first more-or-less-selfless gesture-- ambiguous, though, as everything in Ophuls is. Perhaps Renoir (the allusion to him above being deliberate) could have made these characters more sympathetic, or made us feel more tenderness for unsympathetic characters. (Renoir could make us feel tenderness for a rock.) But Ophuls is not as purely focused on the human heart as Renoir; he always sees the absurd social animal, as well. I think it is more appropriate with Ophuls to have that distancing, as we have when we read "Madame Bovary."

jzappa

A leisurely film because nothing is treated like a more important attribute of a character than anything else, this is nonetheless one of the most affected and elaborate love movies ever filmed. It sparkles and glints, and underneath the finesse it fashions a heart, and shatters it. This French-Italian romance by influential German-born Max Ophuls is known for its complex cinematography, its flowing technique, its sets, its costumes and naturally its jewelry. It stars Danielle Darrieux, Charles Boyer and Vittorio De Sica, who with no trouble manifest cultivated charm because each player is so comfortable in their own skin. It could have been a pretentious gratuity. We watch with great respect for Ophuls' aesthetic fanfare, so fluent and sophisticated. Then to our bewilderment we find ourselves emotionally invested.The story takes place in Vienna a century or so ago. Boyer's General has married belatedly, and luckily, to Darrieux's Madame, an absolute Venus. He gives her exorbitant diamond earrings as a wedding present. As the film opens, Madame is dangerously tapped out, and searching among her accessories for something to sell. The camera follows her in an continuous shot as she looks through dresses, furs, jewelry, and ultimately rests on the earrings, which she never liked anyway. ''What will you tell your husband?'' asks her hireling. She will tell him that she lost them.Standing back slightly from the comings and goings of the earrings, which is the material of sitcom, the movie begins to look more persistently at Madame de... She and her husband live in a time and place where love affairs are pretty much anticipated. "Your suitors get on my nerves," the General carps as they leave a party. If they do not know in particular who their spouse is flirting with, they know in broad terms. Yet there is a discipline in such situations, and it allows fooling around but not love.Smooth, graceful tracking shots occupy every job of the camera, a stationary transience much like the journey of the material luxury and its seemingly vain covetors. The scene where they fall in love exhibits Ophuls' top form. He likes to display his characters encompassed by, even asphyxiating in, their mood. Interiors are crammed with material furnishings. Their bodies are ornamented with gowns, uniforms, jewelry, decorations. Ophuls likes to shoot past a frontal focus, or through a window, to show a characters enclosed by paraphernalia. But in the decisive romantic scene, a mosaic comprising various nights of dancing, the embracing couple is eventually left all alone after such subtle and simple time lapses.As can be expected from bored affluent socialites, the simplest thing becomes a mystery, and leisurely dialogue becomes not about what's spoken, but what is not spoken, or said instead. Hence, "Madame de..." Though there are a few overdone lines which serve more as aphorisms than natural emotional instigations. Ultimately, the film's about the various emotions that can be truly stimulated by material possessions, not just lust for the possession itself.At the crux of this most annoying titled movie is the idea that the worth of the earrings alters in connection with their connotation. At the start, Madame just needs to hustle them. Then, when they are a gift from her lover, they become priceless. An extravagant knickknack, meant to signify adoration, turns out to be an irritation and a hazard when it actually does. It's a great idea.