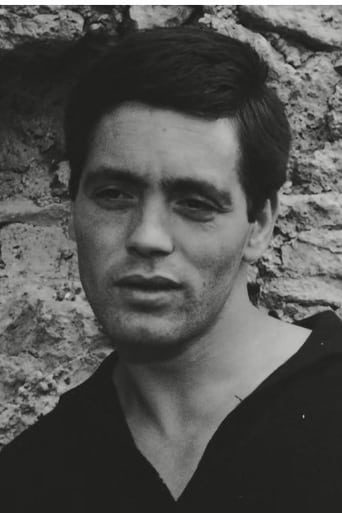

Cristi_Ciopron

In Passolini's synthesis, or blend of realities and fantasy, the realistic intention is very discernible and underlined: it is obvious he meant to give a taste of the Middle Ages as he perceived that epoch, and as he thought things looked like. Hence the flavor of his adaptations—the depiction of a world that is weird, loony, wild, brutal, and evidently godless. He tried to delineate a world that lives out of its own instincts and animal robustness in the biological accepting. It is, needless maybe to add, a leftist reading. Passolini's dire fantasies of orgy and brutality and sacrilege seemed to find a very propitious ground here. The sadness, the intended, meant, deliberate sadness of this movie is tearing-it expresses the desolation and emptiness of a devastated world, witnessed but not cured by an artist's testimony; the aesthetic credo has only a symbolic and ultimately personal value. Not the physical joy, nor the hedonism or sexual beatitude or merriness is at the DECAMERON's world heart—but the sadness. This sadness does not come from a century devastated by fear, anarchy and insecurity—but rather from within—as it is it, the named sadness, who molds the exterior world and enhances and colors the perception. Sad and almost desolate movie; atheism consequently explored and brought to its final deadly conclusions. Passolini was one of the artistically relevant artists. I abhorred SALO, I enormously liked THE DECAMERON, and I see the link between the both—Passolini' s drives, his need for sardonic Fascist (ultimately Nazi) fantasies. I do not mean to denounce him, but to show that what is here sadness is vehemence elsewhere; the man was a decadent, a corrupt man, not only witness but also part of the decay. His medieval fantasy, with its invented realism, is a devastated, sad land, a waste country of cold feverishness and cruelty—yeah, the impression here is one of dry cruelty and meanness and fanatic compulsions brought together by Passolini's sadness. I know that, besides the very obvious naturalism that is fundamentally symbolic, he also meant to bring the sad poetry of a bitter tenderness. Many take his adaptations for the opposite of what they are—for some kind of CARRY ON … popular comedies; on the contrary, they are mean decadent shows pierced by both Passolini's sadness AND his sense and representation of sadness. Aesthetically, his DECAMERON is quite rich; an atheist's credo, violent and grim and cruel and with that fanaticism and grimness and uncanny sharpness that make a better impression here than in SALO. The man was, I repeat, rather rotten and dirty. Nasty also, and twisted. The needed innocence is severely poisoned by sadness and despair. The DECAMERON, work of beauty and gusto, is poisoned by Passolini's radical despair and self—destructive drives; in his case, it seems unavoidable to bring his hidden, secret tendencies and his biography into discussion. He constantly harmed himself ;yet to pity him would be to abase and insult him. He deserves better. With the DECAMERON, he meant something—he meant his own sadness. Waugh spoke about people with the mind of a genius and the soul of an animal; of Passolini the opposite is true. Yet his heart finished by being severely damaged as well. The sex scenes are very good—they look like rough porn by a skilled maestro—the Perronella episode, or the one with the two adolescents. He was an injured, torn and twisted man (and of these things, either inner or exterior, one should speak without phony piety but without inappropriate indiscretion as well), moderately interesting (he was not as compellingly interesting as ,say, Antonioni or even Visconti or Fellini). As a personality, he was patently second hand . Yet he clearly was no Brass either. Put extremely simply, he had something to say; not only he could have had—but he indeed had. He created some things; his interest, therefore, as an artist far surpasses that as a man. He was closer than Visconti, maybe, to the grim, decadent, twisted Neo—Fascist porn aesthetics that will be illustrated by Mme. Cavani, by Brass and Bertolucci (and, of course, the many genre filmmakers). He had a temperament; he was a decadent (no one is structurally a decadent, I presume); these made his films what they are. His films show him mean, cruel, fanatic, and sometimes, as in the DECAMERON, sharp and inspired. When uninspired, he was maybe worse than Zeffirelli; when focused, he was far better, and infinitely sharper. If he, as a man, had any sense for his literary sources, this is far from obvious in his movies. In his thorough and mean atheism, offensive and narrow, he is as mean, delirious and fanatic as Buñuel. He hated the Holy Church as if he did this from Hell. He had not a drop of generosity in him. This tearing sadness is a valid and intended aesthetic result. The product of a decadent creativity and imagination, it is nonetheless imposing. This world of imagination is innerly voided, dramatically emptied and hence mechanical—feverish and cold visions of a waste humanity, excluded from life, left prey to its own base determinism; was this dream the world desired by Pasolini? There is something fundamentally ill and rotten and ailing in this world—almost the contrary of what the book meant. Not a trace of merriment—but a nihilist and sincere, true melancholy and desolation. The heart cut away from the life—and from the source of all life as well. The creation of a man untrue to himself as a man. These subtle values of Pasolini's daring vision are at least interesting as the picturesque and rough sex scenes.

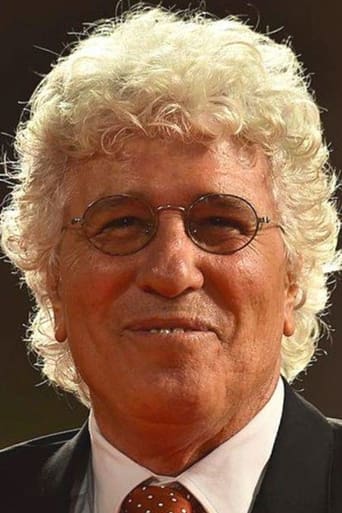

Dr Jacques COULARDEAU

On a sunny day in Naples, a rich young man comes to the market to buy horses. He is tricked by a woman into believing he is her brother and he ends in the tank of the toilet, robbed and soiled. But escaping that trap he finds himself in the street and the scene turns fantastic. The women from their windows tell him to disappear and the men in the street tell him just the same. So there he runs away dressed in his underwear soaked in and perfumed with human feces. His descent to hell in a way. He hides from some nocturnal men in a barrel in some underground cellar but not for long. The men are thieves and they hire him on a mission and there the real film really starts. You will have to go and see it if you want to get the details. Who will die and who will survive, that is THE question in this cruel world. In this film you have to go down into all kinds of holes, tombs, caves, cellars. Pasolini has rewritten Boccaccio with the pen of Dante and he settles accounts with the church first of all, that Italian church that is rich though doing nothing, by doing nothing and exploiting the whole society. And society is then engaged in a simple game, that of recuperating all they can from that church, be it a benediction, be it an absolution, be it a rite of some sort but also some of the stolen money they carry in their clerical purses. So Pasolini makes his characters steal from the dead bishop, and thus steal from his stealing surviving mates. Then they steal from the people in the street, purse pickers they are. They steal some good cheer, comfort, and pleasure from the hypocritical nuns, at least as long as youth grants the young man with enough potency and power and hardness to be able to satisfy the hunger of twenty nuns. They make false confessions not to save their souls but to look good in society when they die and save some trouble to their friends. And of course they steal as much pleasure as they can and absolutely disregard the idea that it may be a sin. Never mind the sin provided we have the pleasure. And this Italy is the Italy of all crimes, of all murders and embezzlements. And of course they all manage to get through but Hell is the destination of them all and the vision of that Hell is superb and in the tradition of its representations in the churches of the end of the 15th century, after the big plague, the Black Death. And yet poetry haunts this film in the very excess it demonstrates. Excess in the language, intonations that you have to enjoy in Italian of course, but also excess in the body language, especially, but not only, facial language. These Italians speak with their full bodies, particularly their hands and their faces. Excess in desire and passion, violence and hypocrisy. Even the morbidity of some scenes becomes artistic in its extreme sadness. And his vision of Hell is superb. Scatology transformed into a great art and that's just the point. The end of the film is the final vision of the fresco some master painter was painting in a church. That painter is the one who had the vision of hell but he transformed it into a civil and elegant scene full of majesty and nobility. He can regret the vision that was so beautiful but he could not render it on the wall of the church. A beautiful film though maybe slightly nostalgic and restrained, which means not entirely free-wheeling along the easy road Pasolini would have liked to be able to take but did not take entirely or in full light.Dr Jacques COULARDEAU, University Paris Dauphine, University Paris 1 Pantheon Sorbonne & University Versailles Saint Quentin en Yvelines

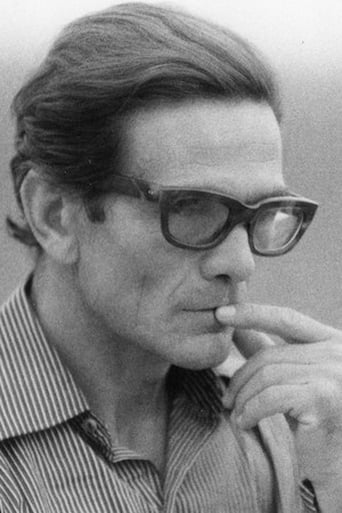

Lee Eisenberg

I remember that I first heard of Pier Paolo Pasolini in John Waters's "Cecil B. Demented", and I interpreted that he was a very arty, non-mainstream director. I then read about how he always infuriated the Catholic Church, and they often took him to court (I get the feeling that his open homosexuality might have also gotten to them), and was brutally murdered in 1975.So, I've finally seen one of his movies. "Il Decameron" (or "The Decameron", depending on which language you want to use) tells several stories of life in a medieval-to-Renaissance Italian village. There's lots of sex to go around (especially in places where it's not supposed to happen), and any gross thing that you can think of will probably happen. But believe you me, Pasolini knows how to make it fascinating; after all, who doesn't love some debauchery now and then? So anyway, this is definitely the sort of movie that you would watch for film history classes and things like that. Not at all a movie for the world's straight-laced factions. But I certainly liked it, and not just because Caterina was really hot. This movie is an important part of film history, Italian history, and other things. You just might want to go to Italy after watching it.