Listonixio

Fresh and Exciting

Adeel Hail

Unshakable, witty and deeply felt, the film will be paying emotional dividends for a long, long time.

Kaelan Mccaffrey

Like the great film, it's made with a great deal of visible affection both in front of and behind the camera.

Taha Avalos

The best films of this genre always show a path and provide a takeaway for being a better person.

Tthomaskyte

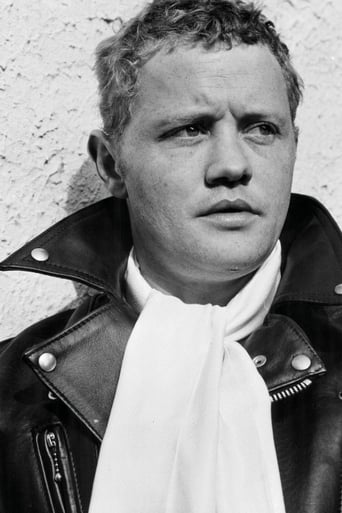

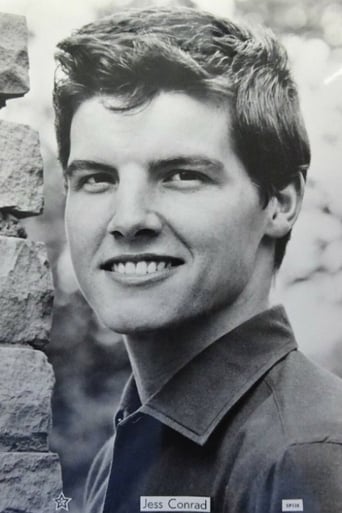

I first saw this when it came out in 1962 when I was almost the same age as the characters on trial. As the film opens we are presented with four resentful and aggressive looking young men on trial for robbery and murder. They are all wearing Italian style suits reflecting the fashion of the time and immediately give the impression of being thugs. We then hear the prosecution's case as delivered by Richard Todd and see flashbacks of the young men (well played by Dudley Sutton, Jess Conrad, Ronald Lacey and Tony Garnett) cutting what appears to be a menacing swathe through London. Next we see the all the same events but from the defendants' point of view but they are now placed in different context by the showing of what happens before and after the events described by the prosecution witnesses. It is a device that has been used before but it still grips here as we are encouraged to challenge our own prejudices. It demonstrates that whenever you see a situation you should not make judgements without knowing the entire history of events.

fillherupjacko

Four young hooligans on the rampage apparently, scandalise intimidate and browbeat their way round the West End before brutally putting to death, with a knife, a night watchman in the course or furtherance of theft.Courtroom drama in which we're shown the same events two different ways, first by the witnesses and then the defendants, so that we don't know whether we're seeing the truth or not. Both versions are similar but the subtle differences are enormous in terms of whether they're innocent or guilty. We're inclined to believe the defendants, at first, that all there is against them is a "farrago of circumstantial evidence", as defending council, Robert Morley puts it. It all actually turns out to be a rather large red herring though.Kids carrying knives gives the film a bit of relevance for today. The boys' teddy boy clothes (actually rather smart) and music by the Shadows (mainly timpani drums) perhaps don't. The whole thing plods along for twenty minutes of events leading up to the crime: a bus to Surrey Docks with nervous conductor Roy Kinnear; a snack bar in a billiards hall; Alan Cuthbertson (who also pops up as a lawyer in Performance – and Twitchin in Fawlty Towers) as a motorist; Wilfrid Bramble (Steptoe) as a toilet attendant; and Colin Gordon, as Gordon Percy Lonsdale, waiting in a cinema cue to see Hungry For Love. Gordon was at the Ministry of Pensions for thirty two years and he's a widower. No wonder he's hungry for love. This is all punctuated by prosecution council Richard Todd telling witnesses in the dock to "take your time - watch his lordship's pencil", and Montgomery (Morley) giving it lots of "I put it to you" in defence. The film comes to life when, "backstage", Morley explodes and starts kicking off on the defendants. "You spread your net of terrorism over half of London…" "Leave him alone you fat, old…" replies Ronald Lacey (Harris in Porridge, Lacey also does a nice little turn in a Sweeney episode "Thou Shalt Not Kill") doing his daft, overgrown kid role. (His ambition is to own a big house in the country and have the Spurs playing on the football pitch "with only me watching, see.")We're left to draw our own conclusion as to why Stan (Dudley Sutton) commits murder: if you carry a knife you're going to use it sooner or later; we're all just one step away from losing control; or maybe it's all down to ineffectual parenting – Stan's dad (Wensley Pithey) can't even be arséd to apply for a council flat while his wife is dying of cancer.All in all this is a great snapshot of a forgotten era.

ianlouisiana

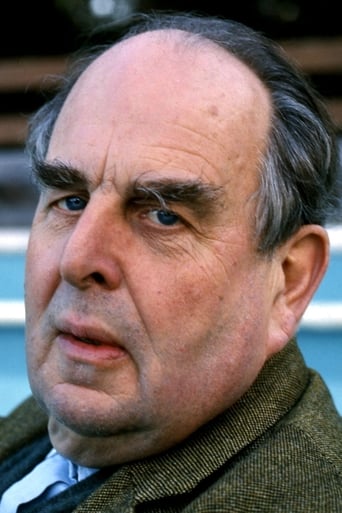

This is a very clever movie and a rather daring one.Anyone who has ever sat through a jury trial either as a spectator or a participant will recognise that the formula "The Boys" uses is based strictly on the court proceedings.The Prosecution,unemotional,cold,precise,outline the case and submit the evidence of the witnesses.As prima facie evidence of the defendants' guilt comes to light,the jury/audience,bombarded with these apparent facts has little doubt of their culpability.By the time The Prosecution has rested there will be a groundswell of opinion that they have proved their case.But then the Defence,declamatory,not fettered by the rules of evidence,highly emotional,puts forward its rebuttal of all that has gone before.Invariably it is given more licence by the judge and invariably it takes advantage of this - as it has every right to do.Doubts about the defendants' guilt begin to creep in.The judge sums up,his parting words being..."The truth,members of the jury,is for you and you alone to decide". In this case it is a Capital Trial,the charge being one of murder in the furtherance of theft,by 1962 one of the few offences that could get you hanged.By then juries were notoriously reluctant to convict for such a crime even if faced with overwhelming evidence.Were "The Boys" just four ordinary lads on a night out,short of money,but determined to make the best of things,or were they the 1960s equivalent of out - of - control so - called feral teenagers,a menace to all who were unfortunate enough to cross their paths as they seek to commit mindless violence? Evidence for both propositions is submitted,the home life of these young boys is examined at some length and just when you might be thinking that they are unfortunates trapped in the seemingly inescapable cycle of low wages,low expectations ,disillusioned and disenfranchised,and now demonised by the police and the disapproving middle classes who are trying to keep them in their place,two of them break down under cross - examination.They were guilty after all. All that is left for the Defence is an impassioned plea for clemency,not unlike that of Orson Welles in the near contemporary "Compulsion". Mr Robert Morley is suitably flamboyant as the Defence Counsel,a man who gives every appearance of having become emotionally involved in the plight of his clients.Mr Richard Todd,the Prosecution,is all business. When he breaks through the boys' lies in the witness box it is just another day at the office to him. The Boys themselves are perhaps a little too lower middle class to appear at home in terrace house and tenement,but the overall feel of the movie is just right for the time. In the end it is the adversarial nature of British Justice that has come under examination.The innocence or guilt of The Boys - two of whom were old enough to be hanged - to be decided in the light of the relative eloquence and ability of their advocates.The message is clear enough - the truth is too precious to be left in the hands of lawyers.Yet what we have in "The Boys" is a demonstration that the law - made in the first place by lawyers -is debated by two lawyers in front of another lawyer who will make a decisison that,likely as not,will later be debated by another panel of lawyers who,in turn,will make a decision that,if it displeases one of the lawyers,will be put before yet another panel of lawyers. Somewhere,under all that lawyering,the truth lies bleeding.

James Hitchcock

Four young working-class lads from the East End of London are accused of murdering a night watchman in the course of a robbery. The film is a mixture of courtroom drama and kitchen sink realism; scenes set in the courtroom are intercut with flashbacks showing the boys' home life and the events of the night leading up to the fatal stabbing. We first see the prosecution evidence and scenes showing events from the viewpoint of the prosecution witnesses. After the prosecution have finished presenting their case, however, the boys get the chance to tell their own story. Shots of them giving evidence in the witness box alternate with scenes showing events from their perspective. As might be expected, the two versions are very different from one another. The prosecution witnesses, representatives of the older generation, all give a one-sided account unfavourable to the young men; their defending barrister tries hard to discredit the evidence of these witnesses and to show that they are ill-disposed towards teenagers. The boys' own evidence suggests that they are guilty of nothing more than youthful high spirits, or at most petty rowdyism, which the older witnesses have misinterpreted as evidence of a violent criminal nature.Given this theme of age versus youth (a common theme in the sixties) it is perhaps unfortunate that, although the boys are supposed to be teenagers, the actors playing them were all in their late twenties. Indeed, Dudley Sutton who played the ringleader, Stan Coulter, was actually a year older than Roy Kinnear who played one of the supposedly older prosecution witnesses.The social realist aspects of the film are well done, giving a vivid picture of the era. (The term "kitchen sink" seems particularly apt in this case, as most of the scenes set in the boys' homes do indeed take place in the kitchen, with the sink very much in evidence, emphasising that for working-class people the kitchen often also served as a dining room and living room). This is not the middle-class "swinging London" that we see in films from a slightly later period such as "Darling" or "Blow-Up", but a London that seems to come straight from the pages of a Colin MacInnes novel, a world of Teddy Boys, coffee bars and billiard halls. To a modern audience it may seem odd that the boys' style of dress should have aroused so much hostility among their elders, as by today's standards they are all very smartly dressed, but in the fifties and early sixties this sort of dandyish appearance was regarded as the hallmark of the violent Teddy Boy movement.The courtroom aspects of the film could also have given rise to an interesting drama, an illustration of the idea that there are always two sides to every story and a plea for greater tolerance by the older generation of the ways of the young. Unfortunately, this side of the film did not work for me. There are two main problems. One is that the prosecution simply do not have a case in the first place. There are no eye-witnesses to the stabbing, no confessions, no forensic evidence, no statements by police investigators explaining why these four boys are regarded as the prime suspects. The only evidence the prosecution call is from members of the public who saw the boys on earlier occasions during the fateful evening, and this amounts to little more than "Those lads struck me as a gang of ruffians". Such evidence would be quite inadmissible under English law; even if it were admissible it would not by itself constitute the "proof beyond reasonable doubt" needed for a conviction. Evidence of a propensity to dress like a Teddy Boy, to engage in horseplay or to commit minor vandalism is not evidence of a propensity to commit murder. Robert Morley gives a characteristically florid performance as Montgomery, Counsel for the defence, but this struck me as a layman's idea of a criminal lawyer, in love with his own rhetoric and more concerned with scoring debating points than with the law. In real life he would doubtless have tried to persuade the Judge to disallow the prosecution evidence and to get the case struck out on a submission of no case to answer.The other problem with this film is that it abruptly changes direction near the end, a reversal of direction which undermines the message about not judging by appearances and being tolerant towards the young. We have been led to think that the boys are innocent, that the case against them is based on nothing more than prejudice, and that the film will end in their acquittal. Then, unexpectedly, Coulter breaks down under cross-examination and admits to the crime. It appears that he and two of his companions are indeed guilty (the fourth is acquitted). The film suddenly becomes an "issue" movie about the capital punishment as Coulter is sentenced to death. We are clearly intended to regard this as an unjust sentence, but Coulter is undoubtedly guilty of having struck the fatal blow; the two others (who cannot receive the death penalty, being under eighteen) are guilty only on a legal technicality. As anti-death-penalty propaganda the film is not very effective; it might have had more impact if the situation had been reversed and Coulter had been sentenced to hang for a crime actually committed by a younger accomplice. (As another reviewer has pointed out, this was the in position the real-life Bentley case).This could have been a gripping courtroom thriller, but was too clumsily handled. At most it is an interesting, but slight, period piece from the early sixties. 5/10