tieman64

In the mid 1990s, a streak of coming-of-age flicks were released, each trying to emulate the tone and style of Rob Reiner's "Stand by me" (1986). "Stand by Me" led to the TV series "The Wonder Years" (1988) which led to Woody Allen's "Radio Days", "Brighton Beach Memoirs", "Man in the Moon" (1991), "Radio Flyer" (1992), "Jack the Bear" (1993), "This Boys Life" (1993), "Searching For Bobby Fisher" (1993), "King of the Hill", "American Heart", "Now and Then" (1995), "Unsung Heroes" (1995), "The Mighty" (1998), "Simon Birch" (1998) etc.These films all employed a romantic visual style which recalled the paintings of Norman Rockwell. They featured older and wiser narrators who reminisced about their childhood days, revolved around small groups of young boys, largely took place in the 1960s and early 70s, and oozed a sense of nostalgia.Essentially, these films were also about the same thing: escape. These kids (or rather their future adult/narrator selves) are all searching for a romanticised version of America. A forgotten - or perhaps nonexistent - age of white picket fences, carefree wandering, pop sodas and family dinners. Behind all this comfortable nostalgia, though, is a palatable sense of menace. Abuse, suicide, murder, the lingering effects of the Vietnam war and drunken fathers, all linger in the background. This trend started in the 1980s, by artists who were born post WW2 and became young men in the turbulent 60s. By the late 1990s the "unseen enemy" of these films stopped being about war, poverty, absent fathers, abuse and alcoholism, and started to be about disease and genetic disorders. Though fading, the idealised Norman Rockwell version of Americana was still there, but now Generation X seemed to obsess over diseases and genetics. For Generation X, misery seemed to be all about ailments and genetic predisposition, like the kids with Morquio's syndrome in "The Mighty" and "Simon Birch" or AIDS in "The Cure"."King of the Kill", a little known film by Steven Soderbergh, is however quite different from all the other films in this wave. Directed by a young man, the film is set in St Louis during the Great Depression, and focuses on a young school boy called Aaron who uses his wits to survive the economic hardships of 1930's America.An imaginative and creative boy, Aaron must survive on his own when his father abandons him, his mother is locked away in a mental hospital and his little brother is sent off to boarding school. Initially Aaron takes to these dilemmas with strong shoulders, but gradually his harsh world begins to suffocate him. He has no food, he's in constant fear of losing his apartment and is mocked by his classmates for being poor. Every misery and mishap imaginable seems to happen to Aaron, but the film, despite being shot in sepia hues, never becomes maudlin or implausible. Soderbergh lets the film unfold like Truffaut, mixing tragedy with a very sensitive, deft touch. Now at first glance the film seems to be celebrating resilience, creativity and that good ole American Spirit. Indeed, the film begins with Aaron reading a story he wrote about Charles Lindberg and the Spirit Of St Louis, the first man and plane to cross the Atlantic. Aaron, like Charles, is a symbol of heroism, persistence, national pride and creativity, a man/boy who triumphs despite the odds.But look closer and something darker seems to be going on. Aaron thinks up a genius scheme to sell birds to make money, but his birds are the wrong sex and aren't worth anything. Aaron then schemes to find the perfect clothes for a school function (in which he wins a top prize), but despite succeeding is teased by his classmates. Aaron, starving and hungry for food, then has enough imagination to cut out pictures of food from a book, but when he eats them, gets sick the following day. Likewise, Aaron is promised food at a restaurant, but the manager refuses the deal and callously turns him away.Now think back to Aaron's scheme to breed birds and sell them for their money. Aaron takes the birds to a pet store and attempts to sell them, at which point the store owner tells him the birds are worthless because of their sex. Aaron agrees and walks away, the camera lingering suspiciously on the store owner for a moment. In an instant we know that this boy is being taken advantage of, and that the store owner stands to gain far more than the boy will.The end result is that the "Spirit of St Louis" is not celebrated, but shown to be the cause of hardship. For one to triumph, another must suffer. For the poor man in the shop to make money, he must rip off a little kid. For a restaurant owner to stay in business, a poor boy must go hungry. In other words, The Great American Spirit is itself a selfish, debased thing, a grand cycle of victors triumphing over others. This, of course, flies in the face of the doctrines and myths espoused by every free-market fundamentalist, despite being backed up by every post neoclassical economist who charts the thermodynamic properties of debt-issued currency. Currency, by the way, is Soderbergh's unacknowledged obsession ("The Girlfriend Experience", "Side Effects", "Contagion", "Che", "Magic Mike", the "Ocean" movies etc).8/10 – Worth one viewing. See "Seven Beauties".

DaveTheNovelist (WriterDave)

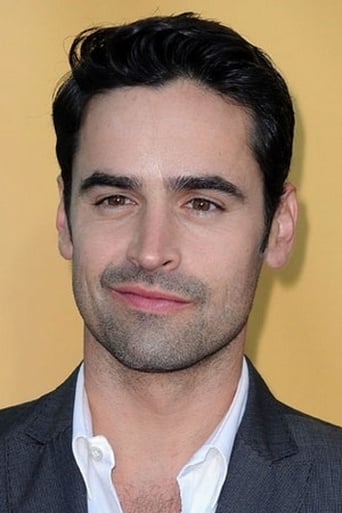

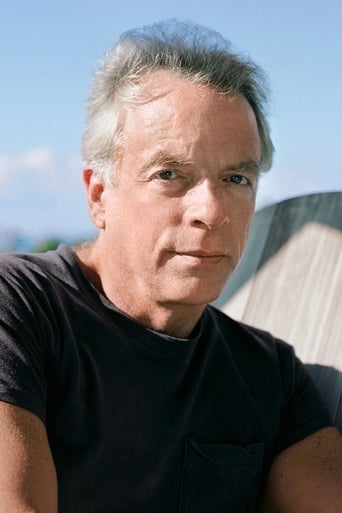

I can recall first seeing "King of the Hill" shorty after its initial release when I wasn't much older than the main character, Aaron (Jesse Bradford, who displays the natural swagger of a young George Clooney here). I was totally enthralled by the story, and this was one of the pieces that ushered in my complete love for and eerie obsession with Depression Era America.Steven Soderbergh as a director over the years has been wildly all over the map traversing genres and styles from top-notch cracker-jack indie flicks (the superb "Limey") to vapid star-studded populist entertainment (the "Oceans" series) to entertaining star vehicles (the excellent "Erin Brockovich") to overblown misguided message movies ("Traffic") to Kubrickian quandaries (the unfairly maligned "Solaris"). In 1993, still in his formative early years, he hit all the right notes with his vividly detailed and heartbreaking tale of a young boy (Bradford) abandoned in a sleazy hotel room on the edge of a Hooverville in 1933 St. Louise by his flaky salesman father, consumption riddled mother, and little brother who got shipped off to live with relatives so he wouldn't starve to death. The boy lies, steals, woos girls and wins academic awards at school propelled only by his keen wit and innate will to survive. Soderbergh brilliantly abandons almost all sentimentality (the exchanges between the brothers are heartfelt but raw, between mother and son tragically subdued, and between father and son frightfully cold yet honest) and views not the actions of the characters through the lens of our modern moral codes, but through the lens of the era in which the characters survived.Special note has to be given to the cinematography, which in lesser period pieces can so easily succumb to stylish excess. The film looks real and puts you right there in the middle of this American quagmire. There's also one amazingly rendered shot of a traffic cop holding up a squealing street urchin by the ear after capturing the boy stealing an apple that is so painstakingly lighted and framed that it serves as the complete flip-side of your classic Norman Rockwell painting from the same era.Viewing this film recently on cable, I was even more transfixed than the first time over thirteen years ago. There's also delight to be found in seeing Oscar winner Adrien Brody in his first major role as Aaron's "big brother" role model, and Grammy winner Lauryn Hill in a nice bit part as a sympathetic gum-chewing elevator operator.Although historically little seen, this film has been universally lauded, and as the early masterwork of an Oscar winning director, it's a crime that there has been no DVD release.