Clevercell

Very disappointing...

Pluskylang

Great Film overall

Rosie Searle

It's the kind of movie you'll want to see a second time with someone who hasn't seen it yet, to remember what it was like to watch it for the first time.

LeonLouisRicci

Considered one of the most Bleak, Depressing, Gloomy, Brooding, but Ultimately Unsuccessful in the Genre of Film-Noir. Unsuccessful at the Box Office and Unsuccessful, but Not Completely with Critics and Fans.It's a Troubled Subject and it was a Troubled Production. The Subject of "Religion" in Motion Pictures in the "Code" Era was Scrutinized as much as Anything from the "Overseers/Big Brother" Censors with Hays Hubris and Nothing Slipped by that wasn't "Christian" Friendly.So this Story of a Young Man who was Dissed by the Church and wouldn't give His Father a "Decent" Burial because of Suicide and the Trauma that Followed was Suspect. But that's just the Pro-Log. His Mother than Succumbs to TB, Dies, and the Trauma is Repeated. Not because of Suicide but because He and His Mother are Ghetto Dwelling Poor.What Ensues is a Film that had to be Pulled and "Softened" with "Book-Ending" New Scenes.The Movie is as Dark as Noir can get with its Relentless Display of an Uncaring and Ugly World, especially if You don't have Money. Audiences at the Time would have none of it and the "Money-Men" at the Studios Shunned the mere Existence of the Film and it Languished in Limbo for Years.The Star, Farley Granger Bad Mouthed the Movie any chance He got and the Film Remained Unrecognized for Decades. Dana Andrews, Paul Stewart and the rest of the Fine Cast all Add to the Agonizing Atmosphere and the Movie Stands on its own. Noble, but Flawed by Fawning Concerns that were Against the Grain of the Source Material.When Viewed Today, it can Showcase Societal Attitudes about Organized Religion, Pulverizing Poverty, and a Studio System, like American Lower Class Life, that was in Dire Need of Liberal Reform in a Post War America that was Showing its Capitalistic Muscle.

dougdoepke

An interesting but not very good movie. It's overlong and too often repetitive. Yet it's also one of the clearest examples of Hollywood's hybrid nature during the studio period. On one hand is the literary desire for hard-hitting social commentary, represented here by novelist Brady (thanks reviewer Songwarrior), and left-wing screenwriter Yordan (my opinion). On the other hand are the studios (including Goldwyn) deathly afraid of defying convention and of boycotting groups like the Catholic Legion of Decency. Here, the tension between these two social tendencies is on clear display.Few movies of the period convey a clearer sense of economic entrapment than this one. No matter in what direction slum-dweller Martin (Granger) turns, he's thwarted by a lack of money and no prospects. Even the parish lacks sufficient wherewithal to help. Sure, the desire to give his dead mom a "proper send-off" seems extravagantly unrealistic. But behind his strident demand is a very democratic desire to be seen as the social equal of anyone else. His protest tellingly never gets beyond the symbolic stage of a "room full of flowers", but unpack it and you get years of frustration, privation, and a dead mother whose only consolation was a priest. Martin may not be very likable, but he is understandable.Stradling's photography underscores that sense of hopelessness. The tenements are bare and dingy, the streets grimy and teeming, even the parish lodgings are spare and uninviting. Only the ornate funeral home presents a contrast, seeming to say that only in death will there be a change. At the same time, the scenes unfold one after the other like episodes in a twilight world of noir. If there's a single ray of actual sunshine, I missed it. No wonder Martin's going slowly nutzoid. Nor, for that matter, are Martin's fellow slum dwellers any help. His neighbor Mr. Craig (Stewart) is a stickup man and practical adviser telling Martin to take what he can because that's the only way to survive. And when Martin yells in the hallway in some distress, the other neighbors look on mutely offering no help. Even the well-meaning old lady can't get her eye-witness identification right. There's no hint here of sentimentalizing the poor. Instead, it's a world of dis-spirited, atomized individuals giving Martin only cursory sympathy for his dead mother. Thus trapped in a hopeless environment, Martin's demand for flowers for mom becomes something much more meaningful.Now, had the role of religion in this bleak panorama been left as it is without the wrap- around prologue and epilogue and without the omniscient narration, the result would have been much less compromised. For, without these later concessions, the priests come across more as "omsbudsmen" than anything else. In short, in its original version (without the wrap-around & narration), the movie portrays the priests as able to intercede with the cops and businessmen, etc. to make life more livable for their benighted flock, but most importantly the original screenplay does not connect them conventionally with the divine. So, the priests viewed in their purely societal role (apart from the soul-saving, divine mission), do perform a worthy assistance function. However, that limited role also lays them open to the charge that they are part of the problem and not the solution since, despite their help, they also do nothing to change the conditions in which Martin, for one, is trapped. They only make life better, not different. And when Father Kirkman tells Martin to "resign" himself to his poverty, a bleakly passive social philosophy is summed up, and much of Martin's unhappiness with the church is lent credence.But, thanks to reviewer Piyork, we learn that original screenwriter Yordan and original director Robson were fired, and the wrap-around and narration added to "lighten" the mood (Film Noir Encyclopedia also lists two production dates). One can imagine the reaction of studio executives on seeing the original version for the first time. With its bleak atmospherics and generally unflattering portrayal of the police and the church, visions of boycott must have danced in their head. Thus what started out as a pessimistic expose of poverty and the church's role ends up making key concessions for popular consumption. Specifically, the church is now connected to the divine— Father Roth refers in the epilogue to: "the immortal soul", "faith is a part of the human soul", "I saw God in Martin Lynn", plus the key implication that apostate Martin is returning to his former faith. The cumulative result is to dilute the original message with an unmistakable supernatural overlay. At the same time, attention is redirected away from social ills to a timeless dimension. As a result, what emerges collapses into an awkward hybrid of noirish pessimism and religious optimism with the final comforting note going to the latter.My gripe here is with Hollywood of the studio period, not with religion or Catholicism generally. Many thoughtful believers (I venture) would be challenged by the original version— that is, by its posing the question of what the actual role of the church (not only the Catholic) in ministering to the poor is? That is, is the church helping or hindering. But then, who's surprised that neither the studios nor the watchdog outfits wanted such fundamental questions troubling popular audiences, at least without conventional answers being supplied. And so another literary work gets processed into near-pablum by commercial Hollywood of the day.Nonetheless, despite the crippling compromises, the novel's original intent still shines through, and if I were reviewer Songwarrior, I would be very proud of my dad.

blanche-2

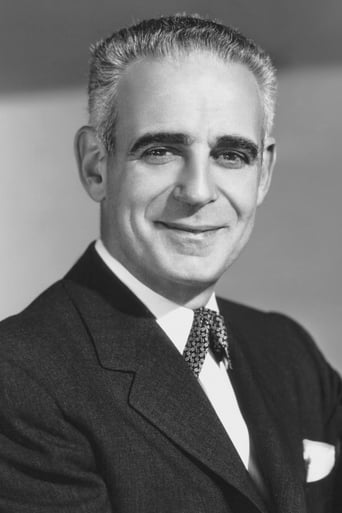

Farley Granger is a young man on the "Edge of Doom," in this 1950 film also starring Dana Andrews, Mala Powers and Paul Stewart. When a young priest wants to change parishes, Father Roth (Dana Andrews) tells the story of Martin Lynn (Granger), saying that what happened with Martin showed him that, as a priest, he was in the right place. Martin Lynn is a young man who is having trouble making ends meet as a delivery man for a florist; he has a chronically ill mother, and he wants to be able to move her to Arizona. However, after working with the florist for four years, he still can't get a raise. When his mother dies, he wants a high-priced funeral for her. He goes to the church rectory, as his mother was deeply religious and, despite living in near poverty, always gave what she could to the parish church. In an ensuing argument with an old, tired and tough priest (Harold Vermilyea), Martin hits him over the head, and the priest dies. Later, he's picked up, not for the murder, but for the robbery of a movie theater actually done by his neighbor (Paul Stewart). Though released, the detective in charge (Robert Keith) is still suspicious of him."Edge of Doom" is a grim noir that never lets up; Martin Lynn can't get a break, not from his boss, the funeral director or the church. His girlfriend (Mala Powers) at first feels there is no place for her in his life because of his mother. After the mother dies and Paul commits murder, he breaks up with her. His only support is Father Roth, whom he doesn't like - he resents the church for not burying his father on hallowed ground when he committed suicide and for taking his mother's money. It's not often in a film that one sees a priest killed - and with a cross yet.The acting is good if not great. Farley Granger is sympathetic as Martin. He was often cast in this type of role. Dana Andrews does an okay job as the priest, but is a little too precious. The way to play a priest is the way Spencer Tracy did - as a man first. Andrews tries to put on a priestly air but it seems forced.Apparently this film was not well received upon release and was withdrawn to add the very beginning, where Andrews begins to tell the story, and the very end, which comes back to the present time with Andrews and the priest. It doesn't really help the film's relentless, depressing tone. Don't watch this one if you need a smile or a feel-good movie.

bmacv

When Edge of Doom was first released, audiences turned away from it with the coldest of shoulders. It was yanked out of circulation so that a pair of bookends could be shot, in which the story becomes a kind of parable told by a wise old rector (Dana Andrews) to a younger priest undergoing a pastoral crisis. The filmmakers shouldn't have bothered: Edge of Doom remains one of the bleakest, least comforting offerings of the entire noir cycle (no mean feat), and probably the most irreligious movie ever made in America. When Farley Granger's devout but tubercular mother dies, it precipitates a rampage against everything that makes up the prison of his life: his ugly urban poverty; his penny-pinching employer who offers promises rather than a raise; the Church, which once refused burial to his father, a suicide, and is now refusing his mother the "big" funeral he thinks he owes her; the smarmy, sanctimonious undertaker. Long story short, he ends up murdering a crusty, hell-and-brimstone priest. The police nab him for a robbery he didn't commit but end up with a different murder suspect. But compassionate pastor Dana Andrews (now in flashback) suspects the truth.... There's something almost endearingly Old Left about the savagery of the indictment leveled against society's Big Guns: Church, police and capitalism. The slum where Granger lived with his mother makes Ralph and Alice Kramden's Chauncey Street digs in Brooklyn look cozily inviting (Adele Jergens, as the slatternly wife of a neighbor, observes, "Smart people don't live here"); outside, the nighttown is noir at its most exhilaratingly creepy. It's easy to see why the public, on the cusp of the fabulous fifties, shunned this movie, whose unprettiness is uncompromised. But it's as succinct a summing up of the noir vision as anything in the canon.