Baseshment

I like movies that are aware of what they are selling... without [any] greater aspirations than to make people laugh and that's it.

SpunkySelfTwitter

It’s an especially fun movie from a director and cast who are clearly having a good time allowing themselves to let loose.

Lidia Draper

Great example of an old-fashioned, pure-at-heart escapist event movie that doesn't pretend to be anything that it's not and has boat loads of fun being its own ludicrous self.

Ezmae Chang

This is a small, humorous movie in some ways, but it has a huge heart. What a nice experience.

dougdoepke

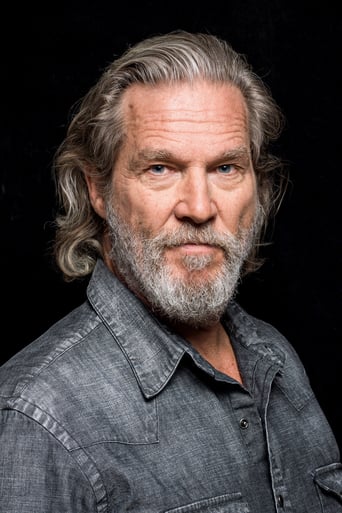

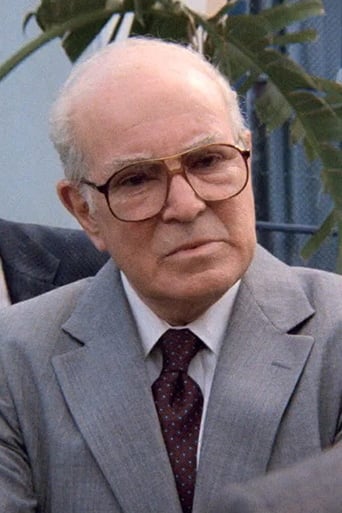

Brilliant allegorical film about wealth, power, and commitment in America. Judging from other reviews, the film does not appeal to everyone. That's understandable. The characters are almost uniformly dislikable, from the abusive Rich (John Heard), to the egotistical Alex (Jeff Bridges), to the self-pitying Mo (Lisa Eichorn), to the slimy George (Arthur Rosenburg)-- there is no one left to root for. At least not until later when the two crippled halves of Bridges and Heard finally unite, figuratively and literally, into one potent whole. Then we realize that it's toward this completion that the twists and turns of the movie have been moving all along. (I think this also explains why the Ann Dusenberry character drops out at a critical stage. She is no longer needed to get the two together.)Rarely has any film dared to create such an unsympathetic cast of personalities, especially Heard's Richard Cutter. If he has a single redeeming quality, I can't find it. His loud, grating voice annoys, piling on one sarcasm after another, oblivious to the hurt he causes. Like Mo he wallows in self-pity, and even shamelessly exploits his disability. Then too, his pursuit of the god-like J. J. Cord should appear noble, yet seems more the result of paranoid rage than a desire for justice. In fact, Heard's explosion of anger on the Santa Monica pier is among the scariest, most convincing expressions of pent-up emotion that I've seen in many years of movie watching. Perhaps he can be charitably viewed as an avenging angel, in the manner of Lee Marvin in Point Blank. But that's a a stretch, since the Vietnam War has left him literally half-a-man, a berserk little top spinning around on alcohol and apoplexy, which, of course, is why he needs the able-bodied Alex to carry out his obsession.Yet Bridge's Alex Bone is an ultimate floater, getting by on boyish good-looks and charm. He has no concerns beyond himself, even seducing the vulnerable Mo, while husband Cutter is away. Apathy is his natural state. So trying to get him to act on the murder he's witnessed is like trying to push a big rock uphill. In fact, when he finally does blend with Cutter's rage and act, it's only because of Cord's arrogant 'sunglasses' gesture, and not because of a sudden steadfast commitment. In most films, it would be the handsome Bone riding the white charger and storming the heavens, having undergone a last minute conversion, and finally giving the audience someone to root for. Here, however, it's the wild spirit of Cutter who rides to the rescue, having at last gotten his legs back if only for a moment. Thus, contrary to expectations, the only concession to Bone is a compromised last minute one.There is, of course, a political subtext to all of this as one perceptive reviewer points out. Perhaps it's about how criminal wealth and power exist beyond the reach of ordinary folks, and how a commitment for change gets dispersed by escapism and a popular feeling of powerlessness, which can only be corrected by what appears a radical form of madness. But allegories aside, this is a bitter brew that does not go down easily. More than that, however, it remains a superb cult film whose provocative characters and perplexing imagery stay with you long after the screen has gone to black.

Lazyl

Did the other reviewers see the same movie? We watched this, remembering it's reputation from the 80s as a good movie. Instead, we got bad American fake noir with a meandering script, one-dimensional characters, and poor Jeff Bridges wandering around looking for a decent scene where he can keep his shirt on. We stopped caring about halfway through, but decided to wait for the prescribed "cat and mouse" game of the CD jacket. Sorry, missed the mouse as well as the cat -- just a couple of weasels running around trying to find justice instead of taking whatever evidence they had to the D.A. like big boys. CW has not aged well -- drunken wife-beaters with drunken wives are no longer considered pathos, just pathetic. Hangers-on who can't make a decision and sleep with their best friend's wives: dopes. Rich guys who are "responsible" for the ills of the world? Sorry -- watch "Chinatown."Best part was recognizing Will Roger's Sunset Boulevard ranch and stable in the final scenes and during the polo match. Otherwise, a waste of time.

dr_alexander_reynolds

I admit I am also very puzzled by the huge predominance of positive reviews given to this movie on this site. The only possible explanation I can see for this is a sort of "virtue by association", since certain features of the film (the presence of actors like Bridges, Heard and Eichhorn; the setting in a seedy milieu with the Vietnam War and Watergate lurking vaguely but potently in the spiritual background) do draw it, superficially, into proximity with masterpieces of 70s cinema like certain films by Bob Rafelson or Arthur Penn. But the proximity is indeed superficial and misleading. "Cutters Way" displays certain stylistic and thematic points in common with the profound, structured, satisfying masterpieces of 70s cinema - but the sad fact is that it is itself neither profound, nor structured, nor - for just these reasons - in the least bit satisfying as a film. We are - or should be - all aware of the dangers of praising "ambiguity" as a meritorious quality in a work of art. I'm sorry, but I'm just not convinced by the implied contention - and in most of the reviews here this contention is indeed only IMPLIED, not frankly asserted and argued for - that Passer somehow made a conscious artistic decision to break with conventional structures of plot and narrative here. The fact that we are left, in the end, radically uncertain whether the man Bridges and Heard are pursuing - and whom Bridges presumably actually kills - committed the crime or not cannot seriously be presented as a dramaturgical or moral strength of the film. The vague piece of empty existentialist piety that some of the reviewers come out with - "the film is not about the need to do any particular thing but rather the need to TAKE ACTION per se" - is one of the most repellently ridiculous things I have ever heard. Does this film seriously propose to us that, since society is vaguely rotten and the true "culprits" of this rotten-ness cannot be reached or even clearly identified, we are morally required to break into the houses of random rich people, who look suspiciously content and well-situated, and murder them? I think we do the director a favour if we choose to classify the utter inconclusiveness of the final scenes as an example of the same narrative confusion and sloppiness as, say, the unexplained vanishing, two-thirds of the way through the movie, of an apparently central character: the victim's sister. I honestly don't see how anyone can fail to get the impression that - far from conveying some deep "symbolic meaning" - the final sequences of the movie were just cobbled together in an attempt to close with as many dramatic and emotional images as possible. Certainly, any psychological coherence that the Cutter character might at some point have had is jettisoned in the last five minutes. After being portrayed for an hour and a half as being doggedly and single-mindedly determined to carefully coordinate the exposure of the Cobb character as a murderer, Cutter's "plan" to do so turns out in the end to consist in nothing more than to go hobbling wildly around the man's house, run away from his bodyguards, jump on a horse he finds in his stables, and then fling himself randomly through some French windows, promptly breaking his own neck. I have no idea whether this scene was present in the original novel, but I must honestly say that this risible spectacle of the hero careening wildly through the garden party - emotionally "beefed up" by some cheap and predictable "subjective camera" shots intended to positively FORCE the viewer to identify with Cutter in a way that his actions themselves make it pretty much impossible to do - seems to me a textbook example of directorial desperation and the frantic attempt to give direction and conclusion, by the sheer illusory spectacle of velocity, to a film that really wasn't going anywhere at all. Sorry, but to even vaguely imply that a messy, confusedly pretentious movie like this can be mentioned in the same breath with 70s classics like "The King of Marvin Gardens" or "Night Moves" is to do grave disservice to the memory of 1970s US cinema.

jonathan-577

Picked this up for a dollar in Victoria, heard nice things about it without any clue what it was about. Turns out to be one of the two or three best scores of my whole VHS-spelunking sojourn this year, a lost almost-masterpiece from the tail end of the seventies' adult drama period, drenched in class consciousness and ironic distance. The characters in this sorta-mystery about some losers aiming to 'get' a mysterious cheerleader-murdering (?) millionaire are unlike any I've seen in an American movie. You feel like you've seen them all before but not on screen. There's something very off-center about the whole picture, from the fascinatingly unpredictable failings of the leads to Jack Nietszche's Morricone-goes-to-LA soundtrack, but it also stands up for commitment in the face of utter futility, an inspirational and timely theme! I can forgive the speechy bits although they stick out like a sore thumb. And who decided to drop Ann Dusenberry in the third act? Her hormonal glare shtick is unlike any dead-cheerleader's-sister in movie history, one more cool thing in a movie that is full of them.